Lab 4: Radio Communication and Full Integration

Overview

One goal of lab 4 was to enable communication between the robot and video controller. After completing this lab, we were able to send information from the robot’s Arduino to our basestation Arduino through a radio. This information included the robot’s current position in the maze, as well as the position of walls at each square. Once our basestation Arduino received this information, we used the Verilog code from lab 3 to correctly display the maze on the screen.

We also worked on full robotic integration for lab 4. Throughout the semester, we have worked on various smaller projects, including motor control, line sensing, the FFT algorithm, the DFS algorithm, robot detection, wall sensing, the FPGA/VGA display, and wireless communication, among others. The other main focus of this lab was to combine all of these components into one working robot and one basestation in preparation for the final competition.

Materials

- 2 Nordic nRF24L01+ transceivers

- 2 Arduino Unos

- 2 radio breakout boards with headers

- 1 DE0-Nano Cyclone IV FPGA Board

Radio Communication

When we obtained the two radio breakout boards, everything was already soldered for us except for the power wires, so we quickly soldered those to the boards and moved on. We then downloaded the RF24 Arduino library and the “Getting Started” sketch, put the radios into two separate Arduinos, changed the channels over which we want to transmit (so that we don’t also receive signals from other groups), and the radios transmitted and received without a problem. We also walked around with the Arduinos and radios and played with the power transmission settings. We found that RF24_PA_HIGH suited our needs (anything below that was too weak, but we didn’t quite need max power).

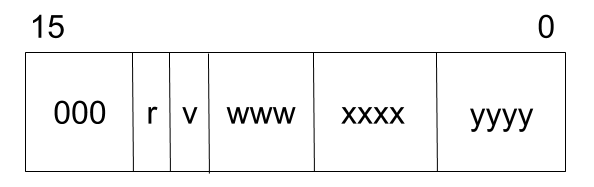

We then wanted to simulate our robot traversing a maze, so we made up a 10x10 array of random wall values and transmitted the message as seen below. Our original scheme involved sending if a robot was detected (r), if the location was visited (v), the walls (www), and the coordinates (xxxxyyyy). For the simulation, we always assumed no robot was detected and the location was always visited. Thus, the scheme looked like the the image below, and part of the code we used to simulate the robot is shown below, as is a video showing the results. We include parts of both the transmitting Arduino’s code as well as the receiving Arduino’s code for completeness.

TRANSMITTER:

byte maze[10][10] = {

B110, B000, B111, B010, B110, B010, B010, B111, B000, B001,

B110, B000, B111, B010, B110, B010, B010, B111, B000, B001,

B110, B000, B111, B010, B110, B010, B010, B111, B000, B001,

B110, B000, B111, B010, B110, B010, B010, B111, B000, B001,

B110, B000, B111, B010, B110, B010, B010, B111, B000, B001,

B110, B000, B111, B010, B110, B010, B010, B111, B000, B001,

B110, B000, B111, B010, B110, B010, B010, B111, B000, B001,

B110, B000, B111, B010, B110, B010, B010, B111, B000, B001,

B110, B000, B111, B010, B110, B010, B010, B111, B000, B001,

B110, B000, B111, B010, B110, B010, B010, B111, B000, B001,

};

msg = 0000000000000000; // Create msg by shifting over current msg and using bit-wise OR

msg = (msg << 1) | 1;

msg = (msg << 1) | 0;

msg = (msg << 3) | maze[x][y];

msg = (msg << 4) | x;

msg = (msg << 4) | y;

// simulate robot in maze

if (x == 9 && y == 9) {

x = 0;

y = 0;

} else if (x %2 == 0) {

if (y == 9) {

x++;

} else {

y++;

}

} else {

if (y == 0) {

x++;

} else {

y--;

}

}

radio.stopListening();

bool ok = radio.write( &msg, sizeof(uint16_t) );

if (ok)

printf("ok...");

else

printf("failed.\n\r");

// Now, continue listening

radio.startListening();

// Wait here until we get a response, or timeout (250ms)

unsigned long started_waiting_at = millis();

bool timeout = false;

while ( ! radio.available() && ! timeout )

if (millis() - started_waiting_at > 200 )

timeout = true;

// Describe the results

if ( timeout ) {

printf("Failed, response timed out.\n\r");

} else {

// Grab the response, compare, and send to debugging spew

byte got_msg;

radio.read( &got_msg, sizeof(uint16_t) );

// Spew it

printf("Got response %x \n\r",msg);

}

RECEIVER:

if (radio.available()) {

// Dump the payloads until we've gotten everything

uint16_t info;

bool done = false;

while (!done) {

// Fetch the payload, and see if this was the last one.

done = radio.read( &info, sizeof(uint16_t) );

uint16_t xcord = (info & B11110000) >> 4 ;

uint16_t ycord = (info & B00001111) ;

uint16_t walls = (info >> 8) & B00000111;

uint16_t visit = (info >> 11) & B00010000;

uint16_t robot = (info >> 12) & B00001000;

}

// First, stop listening so we can talk

radio.stopListening();

// Send the final one back.

radio.write( &info, sizeof(uint16_t) );

printf("Sent response.\n\r");

// Now, resume listening so we catch the next packets.

radio.startListening();

}

Note: This was NOT our final transmission scheme. See Milestone 4 for that. This was just to prove that we could send accurate information over the radios.

Getting the Display Working

At this point, we were able to draw 30x30 pixel tiles at any location on the screen. However, after this lab, we had to actually draw an entire maze, which required some additional work.

Receiving the Radio Data

The first step was decoding the message that we were receiving from the robot’s on-board radio. In the below code, we use the code from Lab 4 to determine when data is available. We used a bit-masking scheme to allow us to send less data and speed up the overall process. We had to extract the data we wanted (wall locations, x and y position) from the radio data. We then saved the relevant data as variables that could then be sent to the Arduino’s output pins, to be sent to the FPGA.

if ( radio.available() ){

// Dump the payloads until we've gotten everything

uint16_t info;

bool done = false;

while (!done)

{

// Fetch the payload, and see if this was the last one.

done = radio.read( &info, sizeof(uint16_t) );

// Spew it

uint16_t xcord = (info & B11110000) >> 4 ;

uint16_t ycord = (info & B00001111) ;

uint16_t walls = (info >> 8) & B00001111;

uint16_t sent = (info >> 12) & B00000001;

x1 = (xcord >> 3) & B00000001;

x2 = (xcord >> 2) & B00000001;

x3 = (xcord >> 1) & B00000001;

x4 = xcord & B00000001;

y1 = (ycord >> 3) & B00000001;

y2 = (ycord >> 2) & B00000001;

y3 = (ycord >> 1) & B00000001;

y4 = ycord & B00000001;

north_wall = (walls >> 3) & B00000001;

east_wall = (walls >> 2) & B00000001;

south_wall = (walls >> 1) & B00000001;

west_wall = walls & B00000001;

global_sent = sent;

printf("Got payload... ");

printf("message: %x", info);

printf("\nx-coord: %d", xcord );

printf("\ny-coord: %d", ycord );

printf("\nwalls: %d", walls );

printf("\nsent: %d", sent );

printf("\n\n");

}

Drawing the Maze

The next step was being able to take the data from the FPGA pins and use it to draw a full maze. At this point, we were able to draw a square in one position, but we weren’t able to draw several in a row. We first had to change how we were sending the data from the Arduino to the FPGA. We found that adding a valid bit was necessary to allow the data to propagate from the Arduino to the FPGA. Without this, we found that random squares sometimes were drawn, or squares were split between several positions.

if (!global_sent) {

digitalWrite( valid, LOW );

delay(100);

drawSquare(x1, x2, x3, x4, y1, y2, y3, y4, north_wall, east_wall, south_wall, west_wall);

delay(100);

digitalWrite( valid, HIGH );

}

First, we wait until the data is available from the radio, then write the valid signal to low, which tells the FPGA to not draw anything. After a short delay, the drawSquare function is called, which writes the correct data to the output pins on the Arduino. After another short delay, we set the valid bit to high, which allows the FPGA to draw on the screen.

void drawSquare(int x1,int x2,int x3, int x4, int y1,int y2,int y3, int y4, int N, int E, int S, int W) {

// x coordinates

digitalWrite( x_pos_1, x1 );

digitalWrite( x_pos_2, x2 );

digitalWrite( x_pos_3, x3);

digitalWrite( A4, x4);

// y coordinates

digitalWrite( y_pos_1, y1 );

digitalWrite( y_pos_2, y2 );

digitalWrite( y_pos_3, y3 );

digitalWrite( A5, y4 );

// WALLS

digitalWrite( A0, N);

digitalWrite( A1, E);

digitalWrite( A2, S);

digitalWrite( A3, W);

}

Once the FPGA receives the data on its input pins, we use Verilog code in DEO_NANO.v to send this data to IMAGE_PROCESSOR.v to be drawn. Since we already completed this part, once we sent the data, the correct tile was drawn on the screen. Drawing a whole maze after this was simple; we just had to send data at every intersection and the display would update itself.

To create the walls, we set the color of the outer border of the tile to a different color than the inside of the tile. In addition to the x and y position of the top left corner of the tile, the wall orientation of each tile would be known and would indicate which sides of the tiles would be colored differently. The code seen below takes in data about where walls are located (north, east, south, west), and then draws the respective area blue if there is not a wall, or red if there is.

n_th <= (north) ? lo_th : 0;

ne_th <= (east) ? hi_th : 30;

s_th <= (south) ? hi_th : 30;

w_th <= (west) ? lo_th : 0;

result <= (xpos < w_th || xpos > e_th || ypos < n_th || ypos > s_th) ? RED : BLUE;

Full Robotic Integration

At this point, we had all of the individual pieces working. We had a wide range of sensors, hardware, circuits, and algorithms that all functioned independently. For the final competition, we had to integrate this all into one final product: a robot that traverses the maze and sends data to the FPGA, which draws the maze. This was probably the most difficult step, but it was definitely the most rewarding, as all of our hard work paid off in the end.

Hardware

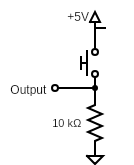

We had created the pushbutton circuit in a previous lab, but for completeness, we have shown the circuit below. It’s a simple pushbutton held low with a pulldown resistor until the button is pressed.

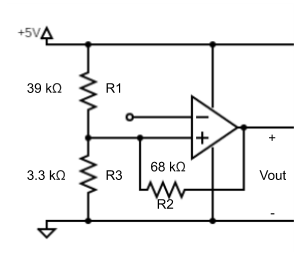

The wall sensors, also working from a previous lab, utilize Inverting Schmitt Triggers so that we could use digital pins rather than analog pins in order to save the pins for other inputs that only work with analog pins. The same schematic from Lab 2 is copied below. We made three of these circuits: one for each wall sensor.

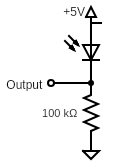

In order to detect other robots, we built another simple circuit that is shown below. We used 940nm IR detectors (shown as the phototransistor below) and played around with the resistor value until we had a large enough range that allowed for easy differentiation between ambient noise (i.e. radiation from the Sun and computer monitors) and the emitters that go on every robot.

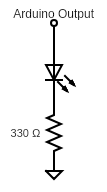

The next circuit we needed to build was an LED circuit that would turn on when we finished mapping the maze. It was yet another simple circuit to build, with the schematic shown below. The green LED is controlled by the Arduino rather than always being at +5V, unlike the previous circuits shown above.

This circuit is exactly the same as our four IR emitter circuits, except that the IR LEDs are powered by +5V rather than the Arduino output.

The final thing we needed to add hardware-wise was support for our fast servos. Powering them off +5V from the Arduino just wasn’t going to cut it. Thus, we used a 9V battery for each servo. The circuit isn’t drawn here because it’s the same thing as powering regular servos, but we wanted to make note that we wired the ground of the battery to the Arduino ground so that we had a common ground, and the +9V terminal went to the power wire on the Servo. The signal that went through the 330Ω resistor from the Arduino to the control wire remained exactly the same.

Software

The software proved far more difficult than anticipated despite the hardware working properly. We integrated the software incrementally in order to aid in the debugging process.

DFS Algorithm/Data Scheme

The first thing we did was completely revamp our DFS algorithm. As noted in the previous milestone, the TAs told us that using recursion and additional data structures like a stack array would probably cause us to run out of memory and cause our robot to fail. Thus, we wrote an iterative DFS using only structs that we defined. Similar to Milestone 3, we created a node struct that holds the position and direction that we always use to keep track of our current location and orientation, and a maze struct that holds a visited bit, a sent bit (for radio communication), and the direction the robot came from in order to reach that location, as well as the location of walls and navigable neighbors around the location. All of these fields use bytes so we can save space. The maze struct is used to make an 81 element array (because the final competition has mazes that are 9x9), with each element representing the location of a square in the maze. Part of the code is shown below.

It is an iterative DFS, so we call dfs() once every time loop gets called. We only want to start moving if the button is pressed so that’s why we have that first conditional in loop. Once the button is pressed, then we want to start the dfs. Then in dfs, we determine our current position and the walls around us, change the neighbors to recognize that we’ve visited the location, determine if we’re done mapping the maze, and then look to move. If we can move, then we do; otherwise, we walk back using the information we’ve saved into the maze. Finally, in loop, when we return to (0,0), we halt. This integrates many things already: the DFS algorithm, the line sensors, the wall sensors, the green done LED, and the pushbutton. A video is shown below the code of this code working on a 4x4 maze.

#define maze_size 81

struct node {

byte pos; // xxxxyyyy

byte dir; // 0000NESW, where only one of NESW can be a 1

};

struct box {

byte vs_came; // vs00NESW, tells if visited with v bit, the walls were sent with the s bit,

// and which direction we came from (where only one of NESW can be a 1)

byte walls_neighbors; // wwwwnnnn, tells where walls are (using cardinal directions) with wwww,

// where is available to move/not move with nnnn (using cardinal directions)

// when nnnn is 1111, everywhere has been traversed and/or there are walls

// so we will backtrack.

};

box maze[maze_size];

node current;

void dfs() {

byte location = current.pos;

// determine the walls around the current location

determineWalls(location);

// set all neighbors such that location is now unnavigable (to avoid repeats)

determineNav(location);

if (determineDone()) { // if we've navigated everywhere we can, turn the done LED on.

digitalWrite(DONE_LED, HIGH);

}

int wemoved = 1;

// if everywhere isn't unnavigable around location

if ((maze[int(location & B00001111) * 9 + int(location >> 4)].walls_neighbors & B00001111) != 15) {

// Now move based on movement priority:

// try in front of us, then to left, then to right, then behind

if (int(current.dir) == 8) { // facing north

if (!moveNorth()) {

if (!moveWest()) {

if (!moveEast()) {

wemoved = moveSouth();

}

}

}

}

// Similar code for other three directions

} else { // if all neighbors are unnavigable

wemoved = 0;

}

if (!wemoved && current.pos != 0) { // if we didn't move,

// i.e. all neighbors have been visited and/or have walls, and we aren't at the start

walkBack();

}

}

... // setup and DFS helpers

void loop() {

if (beginning) { // wait for pushbutton

if (digitalRead(START_BUTTON)) {

for (int i=0; i<2; i++) { // for debugging purposes

digitalWrite(DONE_LED,HIGH);

delay(500);

digitalWrite(DONE_LED,LOW);

delay(500);

}

dfs();

beginning = 0; // stop calling fft if 950 Hz detected or button pressed

}

} else if (!ending) { // to make sure we don't keep doing stuff after we finish

dfs();

} else { // Permanently halt at (0,0) when done.

halt();

}

}

FFT Algorithm

Although we implemented the FFT algorithm that was able to detect 950 Hz earlier in the semester. We found that although our robot was able to detect signals at 950 Hz, it was also very susceptible to noise, which potentially could lead to false starts in the competition. Also, we used a tone generator to collect data that allowed us to determine thresholds for each bin, and collected ambient noise data in the lab. This meant that our algorithm worked well when we used that specific tone generator in the lab in Phillips Hall, but not in other situations. To resolve this, we collected data using the same setup we expected our robot to be in during the competition. We collected data from many samples, with a 950 Hz tone, a 850 Hz tone, a 1050 Hz tone, and finally ambient noise. For the ambient noise, we collected data in Duffield Hall when students were present, since this was closer to the conditions we exppected the robot to encounter in the competition. By analyzing all of this data we were able to develop a pretty simple function to determine which tone was being played based on the values in just three FFT bins.

int freq_detect( int five, int six, int seven ) {

// digital filter on fft output

return ( six > 122 && six < 137 && seven > 120 && seven < 126 && five < 100 );

}

The first four parts in the return statement were threshold values we determined for the sixth and seventh FFT bin. After we ran just this code, we found that it worked very well for 950, but sometimes incorrectly detected 850 Hz. To fix this, we included data from the fifth FFT bin. Since the FFT output of 850 Hz is shifted lower than 950 Hz, we determined that if the fifth bin was above 100, we wanted to ignore it to prevent incorrect detections.

Robot Detection

The last thing we integrated was robot detection. After switching out the wide angle phototransistor and mounting the narrow angled one at exactly 5 inches off the ground, we re-calibrated our detector thresholds. The next part we worked on was combining robot detection with dfs. Our implementation of this was split into two parts: detecting a robot within a call to dfs and within a call to walkBack.

While within a call to dfs, if we detect a robot, we stop our current move to the next node and walk back without marking the current node as visited. By not marking the node as visited, our robot will eventually re-explore that node with our dfs, just at a different point in time.

if (detect_robots()) {

robot_detected = 1;

return 0;

}

As the above video demonstrates, our robot avoids the ‘fake robot’ and moves to the next available node. If there were no available nodes, our robot would’ve turned around and backtracked.

The harder part to implement was what to do when detecting a robot within a call to walkBack since we couldn’t call walkBack within another walkBack call without causing serious memory issues. So in order to work around this problem, we decided to implement a hardcoded avoidance method that wouldn’t mess up our dfs algorithm. After detecting a robot within walkBack, the robot finds a short 3 node path that doesn’t update the maze to take that would ensure we are out of the other robot’s way. Once we finish the short detour, we trace back our steps and move to the exact location where we originally detected the other robot and continue dfs. This way, we completely avoid the other robot while maintaining our position in the algorithm and our maze.

In the following video, our robot accurately avoids the ‘fake robot’ while still exploring every node in the maze.

One could say that our robot just sees a wall and doesn’t move there, but this can be disproven by watching the videos in Milestone 4; it detects the robot and doesn’t send any indication of a wall to the base station.

Below is the code we added in order to implement walkBack robot avoidance.

void movetoLocation2 (byte location) {

// EXACTLY THE SAME AS movetoLocation BUT DOESN'T UPDATE MAZE

// USEFUL FOR ROBOT DETECTION IN A WALK BACK

int diffx = int(current.pos >> 4) - int(location >> 4);

int diffy = int(current.pos & B00001111) - int(location & B00001111);

byte face;

// determine where to face based on difference of current position/position to move to

if (diffx == 1) {

face = B00000001;

} else if (diffx == -1) {

face = B00000100;

} else if (diffy == 1) {

face = B00000010;

} else { // diffy == -1

face = B00001000;

}

// Figure out how to turn the fastest to face the "face" direction (long code omitted for brevity)

// Actually turn to face that direction (long code omitted for brevity)

// Actually move to destination

int go_on = 0;

while ( go_on != 1 ) { // Want to navigate to next intersection at location

go_on = navigate();

}

current.pos = location; // Our current location is now location,

// facing same direction as we were at the time of calling this function

}

...

void miniWalk() {

// Walkback used if we detect a robot during a walk back

byte loc = current.pos;

byte dir = current.dir;

byte path[3]; // Create small path for us to move to in order to avoid robots

int i = 0;

while (i < 3) { // Find 3 open squares and move there, adding them to path

int left = digitalRead(left_ir_sensor);

int right = digitalRead(right_ir_sensor);

int front = digitalRead(front_ir_sensor);

if (front && i > 0) { // Don't want to move straight when i=0 because that's where the robot is!

if (current.dir == B00001000) {

movetoLocation2(current.pos + 1);

} else if (current.dir == B00000100) {

movetoLocation2(current.pos + 16);

} else if (current.dir == B00000010) {

movetoLocation2(current.pos - 1);

} else {

movetoLocation2(current.pos - 16);

}

} // Similar for left and right readings

path[i] = current.pos; // Add new location to path

i++;

}

i--; // Decrement i by 1 to start at i=2

while (i > 0) { // Walk back the path

movetoLocation2(path[i - 1]);

current.pos = path[i - 1];

i--;

}

movetoLocation2(loc); // return to original location where we detected another robot

// Figure out how to turn the fastest (long code omitted for brevity)

// Actually turn to face that direction (long code omitted for brevity)

}

...

void walkBack() {

...

if (detect_robots()) {

robot_detected = 1;

miniWalk();

}

...

}

Conclusion

Overall, the display and radio didn’t prove to be too difficult. The integration was only tough to work out because our fast servos that we acquired made things much more touchy and inconsistent. To deal with this, we simply halted and delayed a small amount at every intersection and performance increased immediately. Things would’ve also been much easier if we hadn’t had to rewrite our DFS, but it didn’t cause us much trouble; it just took time. That’s how everything in this lab went: not difficult, just time-consuming.